St. Vincent Proves She’s the Daddy

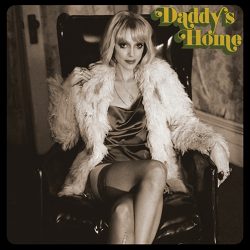

The version of St. Vincent on Daddy’s Home has emerged in tinted shades, bell-bottomed power suits and a curled bob in a collection of 70s ensembles taken to deliciously campy levels.

Annie Clark is a chameleon. The artist created St. Vincent so she could experiment with an infinity of personas, sidestepping the confines of personal branding to which so many musicians are tethered. Rocking everything from futuristic pleather suits to 80s spandex leotards, past iterations of St. Vincent earned Clark Grammys for her slick electronic sound and juggernaut guitar shredding.

The version of St. Vincent on Daddy’s Home has emerged in tinted shades, bell-bottomed power suits and a curled bob in a collection of 70s ensembles taken to deliciously campy levels.

Somewhere, David Bowie is smiling.

It’s not all kitsch—Daddy’s Home is a technically masterful album. Clark commands her guitar, creating psychedelic undulations while simple drums shimmer and a power-packed chorus cries soulfully across the sound. It’s a superb sonic mirage.

Rife with dirty organ riffs and bursts of saxophone, the title track—Daddy’s Home—references her father’s release from prison after participating in a multimillion- dollar stock manipulation scheme. In The Melting of the Sun, Clark pays homage to female performers—icons like Joni Mitchell, Nina Simone and Marilyn Monroe— who were suppressed by an industry and a time that refused to hear their voices beyond their microphones and silver screens.

Clark’s seventh studio album is both glamourous and tough, fusing layers of personal struggles, retro influences and nods to old school legends with such masterful execution that it’s clear the real daddy is Clark herself.